I shall be the villain

The way that Malcolm X and Martin Luther King are remembered is very limiting to both. MLK is presented as a saint, a non-violent campaigner for human rights, the perfect hero. Malcolm is portrayed as militant and the perfect villain. The blog will explain how Malcolm is misused while MLK is wrongfully appropriated to suit Americans themselves, highlight some of the most amazing features of Malcolm X, and show how two starkly contrasting figures can complement each other and be equally important for the same cause.

The

question usually posed regarding the civil rights movement is that does a

revolution need MLK or Malcolm, or both Malcolm and MLK?

As Colin Morris, the author of Unyoung,

Uncolored, Unpoor wrote, “I am not denying passive resistance

its due place in the freedom struggle, or belittling the contribution to it of

men like Gandhi and Martin Luther King. Both have a secure place in history. I

merely want to show that however much the disciples of passive resistance

detest violence, they are politically impotent without it. American Negroes

needed both Martin Luther King and Malcolm X …”

Even though I personally agree with King’s politics of

non-violence much more, and agree mostly to Malcolm’s post Nation of Islam and

post-Hajj years, what I hope to show is that you do not necessarily have to

accept one and reject the other.

Malcom and MLK addressed

different problems of black people. James Cone has remarked that Malcolm tried

to liberate black people from hating themselves while MLK tried to liberate

white people from hating black people. Which makes it ironically tragic that the

trigger pulled on MLK was by a white hand, and the trigger pulled on Malcolm

was by a black hand. Each had grown up under different influences; MLK under

the NAACP influence while the Garveyite influence was strong on Malcolm

explains his racial segregation advocacy. In the words of the great James

Baldwin:

“As concerns Malcolm

and Martin, I watched two men, coming from unimaginably different backgrounds,

whose positions, originally, were poles apart, driven closer and closer

together. By the time each died, their positions had become virtually the same

position. It can be said, indeed, that Martin picked up Malcolm’s burden,

articulated the vision which Malcolm had begun to see, and for which he paid

with his life. And that Malcolm was one of the people Martin saw on the

mountaintop.”

The great thing about both

men is that their growth. The ideologies of both changed with time; Malcolm

left his racial segregation advocacy while MLK became more militant by the end

of his life; thus, becoming closer to each other. But both men are often limited

to one aspect of their characters. MLK is limited to his ‘I have a dream’

speech, and his later more stringent critiques of white supremacy is ignored. Only

that part of MLK has been appropriated that is acceptable to white America.

Malcolm is his violent counterpart and is limited to that. As explained later,

this was a role he then willingly took on. However, Malcolm was never militant:

“I don't favour

violence. If we could bring about recognition and respect of our people by

peaceful means, well and good. Everybody would like to reach his objectives

peacefully. But I'm also a realist. The only people in this country who are

asked to be nonviolent are black people.”

Malcolm found it

hypocritical for blacks to commit to non-violence when they were at the

receiving end of state sponsored violence, which is a very respectable stance. He

was right too. The only time America passed gun legislation was when the black

panthers got armed!

There were plenty of reasons to vilify Malcolm. He really was that dangerous! However, not in a militant way. Malcolm was an internationalist and eventually became a pan-Africanist. On the superior attitude Americans had towards Africa, he said: "They cripple the bird's wing, and then condemn it for not flying as fast as they". In his last year, he travelled extensively and shamed US on a global level by exposing the racialized oppression. He called on African leaders to take action against America's oppression of blacks. In the backdrop of the cold war, this was detrimental to America's foreign policy and its image of supposed moral superiority, and was used by the Soviet Union. He was also the first civil rights leader to condemn the Vietnam war and link colonialism to what was happening inside the US. He went to Gaza and uplifted the cause of Palestine, and was stringent in his criticism of European colonialism and, what he called, "American Dollarism". His great contribution was that he internationalized the black struggle through his pan-Africanism: "I want to dismantle the entire system of racial exploitation".

There were plenty of reasons to vilify Malcolm. He really was that dangerous! However, not in a militant way. Malcolm was an internationalist and eventually became a pan-Africanist. On the superior attitude Americans had towards Africa, he said: "They cripple the bird's wing, and then condemn it for not flying as fast as they". In his last year, he travelled extensively and shamed US on a global level by exposing the racialized oppression. He called on African leaders to take action against America's oppression of blacks. In the backdrop of the cold war, this was detrimental to America's foreign policy and its image of supposed moral superiority, and was used by the Soviet Union. He was also the first civil rights leader to condemn the Vietnam war and link colonialism to what was happening inside the US. He went to Gaza and uplifted the cause of Palestine, and was stringent in his criticism of European colonialism and, what he called, "American Dollarism". His great contribution was that he internationalized the black struggle through his pan-Africanism: "I want to dismantle the entire system of racial exploitation".

These are enough

reasons for Malcolm to remain unacceptable to America. However, what is ignored

is how close King came to these stances too. King took on opposing the Vietnam war

later too. He lost a ton of support consequently, and even called “my own

government” as the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world”. The

possibility of a solidarity between the two greatest leader of the Movement was

increasing who had hitherto been viewed as the opposite ends of a spectrum.

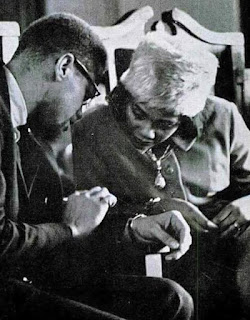

Then a picture was clicked; that of their only meeting in 1964. That picture haunted

America. When King went to Selma in 1965, Malcolm sent him a telegram saying

that he would send people to teach the blacks there self defence if King’s

demands were not fulfilled. He sent a telegram to the neo-Nazi George Lincoln

Rockwell the same day threatening him “ This is to warn you that I am no longer

held in check from fighting white supremacists by Elijah Muhammad’s black

separatist movement, and if your present racist agitation against our people in

Alabama causes physical harm to Reverend King or any other black Americans who

are only attempting to enjoy their rights as free human beings, you and you Ku

Klux Klan will be met with maximum physical retaliation from those of us who are not handcuffed by

the disarming philosophy of nonviolence and who believe in asserting our right

of self-defence…by any means necessary”.

But he never outlined what those means were. He is intentionally

ambiguous in his last months. The fright this level of solidarity must have

raised, perhaps explains the soon followed assassination of Malcolm, for the

NOI were not his only murderers. James Baldwin famously blamed the white press

for his murder saying, “You did it!”

However, how Malcolm chose to bring

about this unity is extraordinary. Rather than working with King in agreement,

he embraced his role of villain he had been given. His historic words to Coretta

Scott King were: “Let me be the scary alternative to Dr. King so that Dr.

King’s goals can be achieved. They fear me more than you and if they see me

coming around, then they’re gonna be more willing to accept your demands because

they don’t want to see Malcolm’s flavour bleeding into the south”.

What inspires me so much about this

is how the trickster and the minister can work for a similar cause, not by

working together, but against each another; but in the end, complementing each

other. Intentionally.

Bibliography

Comments