International Communism

Proletarians of all countries, Unite!

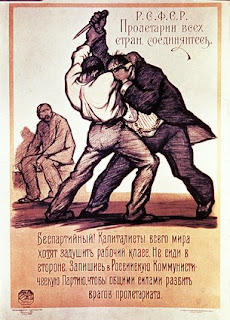

When we discuss the Communist utopia as envisioned in Leninist ideals, classlessness is the ultimate professed aim: class differentiation being an inequality to be eventually remedied. In theory, racial and cultural differences were dismissed and subordinated to the true identifier of economic class. As such, the idea of an international communism, while implicitly accepting the nation-state as the fundamental unit, did posit a transcendence of these differences essentialized in the ultimate identity of the worker or proletarian. The poster above confirms and illustrates the Soviet aspiration of racial/national/cultural differences melting away in the face of class struggle and toppling the bourgeoisie.What seems to be deliberate here is the racial ambiguity in the depiction of each character. Faces are almost absent from the picture, and one is to distinguish between the proletarian and the capitalist on the basis of their body and clothing. Both Claude McKay and Dada Amir Haider Khan, in their accounts of their respective sojourns in Russia, do contrast this experience with the racial discrimination that defined American society. Whilst Khan writes of a gentle acceptance (contrasting it with the colourism he witnessed in America which led him to experience an “inferiority complex”), McKay writes of what appears to be almost a celebration of his person: “Never in my life did I feel prouder of being an African, a black, and no mistake about it. Unforgettable that first occasion upon which I was physically uplifted. [...] As I tried to get through along the Tverskaya I was suddenly surrounded by a crowd, tossed into the air, and caught a number of times and carried a block on their friendly shoulders”. However, his presence there as the token African-American expected to speak for all persons of his race (as when he was urged to make a speech at the Bolshoi theater) is not ultimately lost on him. While he takes everyone’s manner toward him in stride because it seems ultimately benign, his narrative does feature instances of blatant racism as when the Communist member of British Parliament, Newbold addressed a member of the Chinese Young Communists as “Chink”.

When we discuss the Communist utopia as envisioned in Leninist ideals, classlessness is the ultimate professed aim: class differentiation being an inequality to be eventually remedied. In theory, racial and cultural differences were dismissed and subordinated to the true identifier of economic class. As such, the idea of an international communism, while implicitly accepting the nation-state as the fundamental unit, did posit a transcendence of these differences essentialized in the ultimate identity of the worker or proletarian. The poster above confirms and illustrates the Soviet aspiration of racial/national/cultural differences melting away in the face of class struggle and toppling the bourgeoisie.What seems to be deliberate here is the racial ambiguity in the depiction of each character. Faces are almost absent from the picture, and one is to distinguish between the proletarian and the capitalist on the basis of their body and clothing. Both Claude McKay and Dada Amir Haider Khan, in their accounts of their respective sojourns in Russia, do contrast this experience with the racial discrimination that defined American society. Whilst Khan writes of a gentle acceptance (contrasting it with the colourism he witnessed in America which led him to experience an “inferiority complex”), McKay writes of what appears to be almost a celebration of his person: “Never in my life did I feel prouder of being an African, a black, and no mistake about it. Unforgettable that first occasion upon which I was physically uplifted. [...] As I tried to get through along the Tverskaya I was suddenly surrounded by a crowd, tossed into the air, and caught a number of times and carried a block on their friendly shoulders”. However, his presence there as the token African-American expected to speak for all persons of his race (as when he was urged to make a speech at the Bolshoi theater) is not ultimately lost on him. While he takes everyone’s manner toward him in stride because it seems ultimately benign, his narrative does feature instances of blatant racism as when the Communist member of British Parliament, Newbold addressed a member of the Chinese Young Communists as “Chink”.

Meanwhile, without prejudice, Dada Haider Khan’s account insists on noting the ethnicity of everyone who accompanied him as a student and as a traveler on his trip, and while this may not carry notions of bias and perhaps only serves to emphasize the transnational character of the enthusiasm for Communism, it does ultimately establish the primacy of race/ethnicity as an identifier, even in that setting. McKay’s account itself betrays the geographic dimension of wealth inequality when he describes people in Moscow as having “Oriental raggedness” not characteristic of cities such as London, New York, and Berlin. His own tendencies of romanticizing the orient are captured in his appreciation of artwork depicting him traveling over African jungles on a magic carpet, decidedly Arabian Nights-esque in nature, an instance far too loaded to unpack here. Ultimately, we cannot explore all the implications of racial identity, imperialism, slavery, and orientalism in so limited space but perhaps this can only serve to highlight how the Communist ideal of international class solidarity was so divorced from ground reality even in its nascent, optimistic form, among its very champions.

Comments